Battleship Potemkin

Made: 1925

Cast: Aleksandr Antonov, Vladimir Barsky, Grigori Aleksandrov, Prokopenko

Director: Sergi Eisenstein

Screenwriter: Nina Agadzhanova

Cinematographer: Ed Tisse

"DEATH TO THE OPRESSORS!!!"

One of the most interesting about this movie is how the music helps it tell the story. The director Sergi Eisenstein wanted the soundtrack to be rerecorded every twenty years so each generation could have its own soundtrack to rebellion. He underestimated his own ambition: it started off being re-recorded every twenty years or so, but then it became every ten years to five years and these days it's done yearly. What rings true with this theory of music is that Battleship Potemkin plays mostly like a techno rave: It gets the blood pumping and makes the viewer a part of its experience. However there are moments of silence and contemplation, creating a perfect viewing experience. It seems his idea of rebellion struck a chord with every generation. It was a fairly open art form, silent cinema, and though many interesting movies had been made before, 1925's Battleship Potemkin pushed the art form forward like nothing else ever before. It had an attitude. And that attitude was not friendly.

The rebellion that began on the battleship spreads soon to the major cities of Russia and of course, is put down by the oppressive government. Potemkin remains one of the more violent movies ever made; violent in spirit. The Battleship revolution, dramatized: the sailors who complain about poor living conditions are to be executed but the leader of the rebellion, Valkulinchuk, yells, "Brothers who are you shooting at?" The rifles waived. The intense building music stops. They are swayed, just as the audience is, to rebel against their leaders. The following rebellion is one of the more interesting bloodless yet graphic scenes of violence ever made. The officers of the desperately try to shoot the sailors, but they are outnumbered. They try to climb on pianos and secure ropes on high ground, but they are dragged to the floor and stomped to death. The cruel captain who wanted the sailors to eat maggot-filled meat gets no mercy; he is kicked, beaten, dragged up the stairs backwards, has his bones crushed and then is thrown in the ocean. When the rebellion's leader Valkulinchuk is shot, he falls suspended by a rope clinging for dear life in one of the movies more memorable images. He is dragged out of the ocean and the words, "he who was the first to call for an uprising fell at the hands of a butcher." Making him a martyr, a la Jesus Christ.

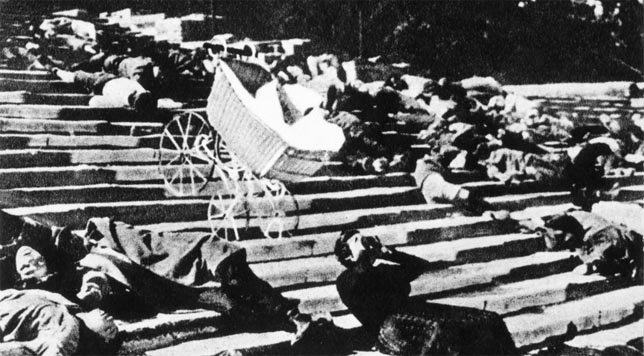

When the scenes change to Odessa, it is surprisingly happy, as if to attach us to its characters. Then suddenly, (as the subtitles even say) all of the rebellious people of the town run down the stairs as the soldiers approach in white uniforms forming a single file line. The music speeds up, and the soldiers start murdering everyone. A child is shot in the back of the head and his mother screams and pleads for his life amidst the stampede of people running. Another mother carrying her baby slowly down the stairs is shot in the gut, and her baby falls step by step amongst the crowd heading for certain doom. The shadows of the soldiers stamp out the life of the people, including the last spectator who has her eye blown out of its socket by a rifle. Action movies are born here, with different types of stories all intersecting and crossing over each other; stacked on "top" of each other like Eisenstein and his editor Grigori Alexandrov theorized. These scenes are endlessly parodied and homage to in movies today, most notable in Brian De Palma's The Untouchables and Terry Gilliam's Brazil.

Einstienen's message was to influence political thought with emotional responses. To achieve this, he introduced his theory of "montage", and effected every movie ever made after it. Despite all the chaos, there is a mathematical precision to each scene and it is edited perfectly; some would say "too perfectly". There are no main characters, only people as symbols for ideas. It probably could have been a longer movie then 75 brief minutes, but would it have had the same effect? There are 5 parts to the movie and each segment is close to the same length. It does not flow; the scenes hit you like fastball pitch after fastball pitch, piled on top of one another. In a way, Potemkin is like a documentary on how to make effective movies. It lets you know you are watching a movie, HERE IS WHERE THIS SHOULD HAPPEN it what it might as well be saying. It sure was nice of Eisenstein to point that out for us. Some of his other films (Oktober, Ivan the Great, Andrew Nevsky, all great films as well) had the same methods and cultural socialist messages, but Potemkin transcends all that. It is a movie that speaks its mind, and back in 1925 no one had created images quite like these.

What exactly is Battleship Potemkin's message then, after 90 years? It definitely gets you riled up for rebellion and holds your interest. Very few movies get better over time like this one does. After all the gleeful carnage, there is sort of an aftermath on board the ship, almost as if they are contemplating the horror of what has transpired. A requiem of sorts, awaiting safe haven from the possible enemies on a neighboring ship. Is there a point to all of the violence and uprising, or is it saying an eye for an eye is not the way? There is one man when the revolution begins who actually screams, "kill the jews!", and is then beaten to death by the mob! We should feel happy that the racist is dead...or should we? There is only one person in the entire movie who stops for reasoning, who questions all the rebellion's violence, and I'm pretty sure she is the one who gets shot in the brain. There is a deeper message to Potemkin then "violent rebellion", something brewing below the surface. Rebellion of the mind, rebellion of prisons and of shackles, rebellion of normality. Politics come into play, but you don't have to be a Russian in the 1920's to enjoy the movie. This deeper message makes it one of my favorite movies.